My Story: Patsy Walker

Part Four

TITLE: My Story: Patsy Walker – Part Four

AUTHOR: Patsy Walker

PERMISSION to publish granted by the author

Patsy Walker was born on May 16, 1934 in Knoxville, Tennessee. In December of 2024, about eight months after her husband Moe passed away, she wrote to the Wilma Dykeman Legacy and requested a copy of a Knoxville News-Sentinel column which Wilma wrote in 1977, just after Wilma’s own husband had died. “I loved her writings so much,” Patsy wrote, “but the one about [her husband’s] death just spoke to me! I think it has been my favorite love story of all times! I kept the clipping all these years and was devastated to misplace it after my husband’s death.”

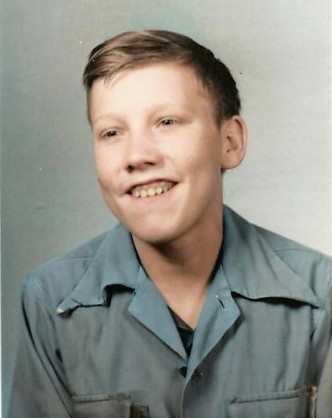

As Patsy and the Legacy corresponded, it became evident that she had written down her memories from growing up in northwest Knoxville. The Wilma Dykeman Legacy is proud to publish these memories for the first time in order to enrich the flesh-and-blood history of Knoxville during the mid and late 20th century. The photograph is of Moe Walker on the left and three childhood friends (Pete, Dean, and Cotton).

“It’s not been an easy life,” says Patsy, “but it’s been a good life."

Moe Walker, neighbor

Moe [Walker, Patsy’s future husband] was born at 305 Leslie on February 23, 1934, about two blocks from where I was born. At that time, the doctor came to the house and delivered the baby.

Preacher Williams’ store was across the street from 305, and the Arrowood house was to the right of Williams’ store. Mickie Arrowood and Moe were best friends growing up. They played together, went to school together, and spent the night with each other.

The neighborhood boys played Tree Tag in nearby Webber’s Woods. This consisted of jumping from tree to tree and tagging someone. If you were tagged, you were “It” and you had to tag someone else to be “It”.

Moe’s house was alive with activity – lots of people coming and going. One day Jay Walker [Moe’s brother] rode double on a bicycle with Bill Arrowood to Morristown. When they got to Bud Sexton’s house, he wouldn’t let them come back to Knoxville (40 miles away) because it was too late. The next morning Bud had the milkman take them home in his truck. Jay said when he walked in, no one seemed to notice he’d been gone all night.

Bill Arrowood was quite a prankster. He had a dummy girl that he liked to scare people with. He would tie a string around the dummy and put her in a tree. When a car came down Leslie Street, he’d let the string drop the dummy in front of the car, and then he’d jerk the string back up into the tree. By the time the driver stopped the car and got out to look, the dummy was nowhere to be seen! I’m sure a lot of poor old drivers were scared out of their wits, thinking they’d run over a person. Sometimes he’d put the dummy in the rumble seat of his car and drive around town with her just flopping in the back of the car.

The Wagners lived to the right of 305 Leslie, and behind them lived another family of Wagners facing Webster’s Alley. Saturday night was bath night for most families. We’d get a galvanized tin tub, fill it with hot water heated on the wood stove, and begin the Saturday night ritual. At my house, they started with the oldest kid and worked down to the youngest. The Wagners’ kitchen window had a curtain half-way up the window, with nothing on top. From a tree you could see into the kitchen. So guess what the boys did on Saturday nights. They climbed the tree and watched the chubby (actually fat) Wagner women take their baths. What a way to spend your evening! But remember: no TV’s, no video games, no computers, and usually no phone (and for a while, no electricity). When you did get electricity, you’d have a single light bulb hanging from the ceiling.

Leslie Street was a mixture of good and bad: a few middle-class people, a lot of poor folks, and then there were the bootleggers. Diddle Viles was one of them. He kept moonshine hidden all up and down Leslie Street under the water meter covers. My Papa Wade also sold whiskey and did chicken fighting on the side. When one of his roosters died, Uncle Ted [Roberts, Mama’s brother] and Jay decided to have a funeral for him. Jay said Ted was the preacher, and his sermon was, “I tell you, this chicken died!” Papa’s main work was at Cherokee Mills, a textile mill where they made cotton fabric [Cherokee Mills was in Knoxville from 1917 to 1954]. A lot of the folks I knew worked there. It was located on Sutherland [Avenue] and was an easy walk from our neighborhood.

In those days, it wasn’t necessary to lock your doors. Neighbors were welcomed whenever they came, and the evenings were spent sitting on the porch talking or telling stories. Most of our friends didn’t have a car. We walked to work, to church, to the store, to school and to neighbors. On Saturdays, we’d take the bus to “uptown” (Gay Street). The bus was so crowded, you’d have to stand up until some of the people got off at their stop. The “colored” people had to ride in the back of the bus. They also had separate bathrooms in the department stores, separate water fountains, separate theaters and were not allowed to eat in "our" restaurants. In retrospect it was very,very wrong, but we thought nothing of this because that was the way it had always been.